The Decline and Fall of Stabilization

The political struggle for controlled marketing had been won. It remained to be seen, however, if the scheme would succeed in the face of opposition from independent shippers and those growers who had fought the plan all alongparticularly since the legislation did not take the ultimate step of giving the growers control of the agency, but left that power in the hands of the shippers.

The Produce Marketing Act, as finally passed by the Legislature, was essentially the measure requested by the B.C.F.G.A. It set up immediately an “Interior Tree Fruit and Vegetable Committee of Direction”, with exclusive power to control and regulate the marketing of all tree fruits and vegetables in an area basically comprising the Thompson, Okanagan, and Kootenay regions; other areas and categories of produce could be similarly established by a favourable vote by 75% of their producers. The Committee had legal power to control marketing of Interior fruit within Canada (exports were not under its jurisdiction), and to fix quantities, prices, and times at which fruit might be marketed by the shippers. In practice, however, the Committee could not set prices or even control shipments, but only apportion orders to shippers on a pro rata basis. Even so, it stopped at least some of the cut-throat competition and thus steadied prices, which remained relatively stable during its period of operation.

The government-appointed Chairman of the Committee was Francis Molison Black, a former member of the Manitoba Legislature. He had experience on both sides of the marketing fence, having worked as treasurer both for P. Burns and Company, the meat-packer, and for the United Grain Growers.

The Committee of Direction was to finance its operations by a nominal licensing fee for shippers, and by a levy, assessed on growers through their packing houses, of 1% cents a box on apples and pears, one cent a crate on other fruit, and fifty cents a ton on bulk fruit and vegetables. From the start, the Committee met resistance, particularly from Doukhobors in the Kootenays and Chinese potato growers in the Kamloops- Mainline area, over licensing, deduction of levies, and prices and conditions of sale set by the Committee. These difficulties were accentuated by the reluctance of the provincial Attorney-General’s Department to instruct the Provincial Police to enforce the Act.

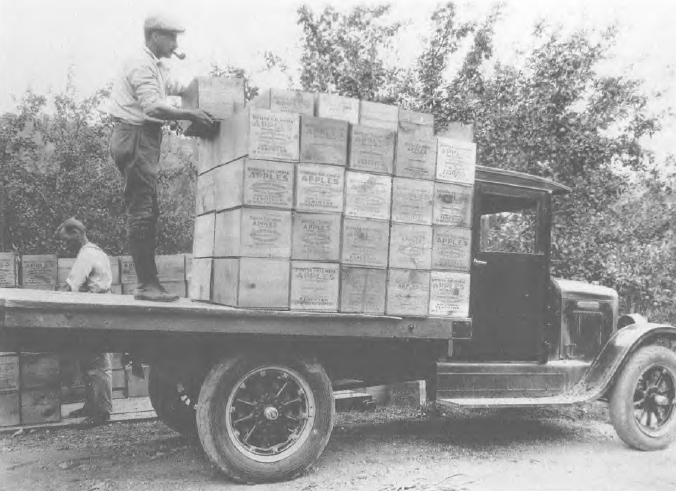

However, 1927, the first season of operation, was favourable. The Committee was materially aided by the smaller crop, nearly a quarter less than in 1926, so the average price of a box of apples, f.o.b. the packing house, rose thirty-two cents over the 1926 price, to $1.52. There was a problem with some shippers who tried to gain a selling edge by secret rebates to jobbers,4 but abuses were limited because, for the first time, the coordinating agency had the legal power to punish offenders. Most shippers were willing, once the furor over the passage of the Act had died down, to give the system a trial, and the vast majority of growers were in favour.

The results of expanded plantings before and after the Great War were still putting new strains on the industry, however, and the crop of 1928 was the largest on record. Average returns on apples dropped by over twenty cents a box. The Committee had some effect on the market, but it certainly did not live up to the expectations of those who had agitated for it two years before; internal competition had not been eliminated and the Committee did not even try to apportion markets fairly among shippers. As usual, Associated Growers found itself saddled with selling a disproportionate share of its crop on less profitable export markets to stabilize prices.

The 1929 B.C.F.G.A. Convention showed that the honeymoon was over: members criticized Committee operations and Committee members tried to excuse themselves from blame. A resolution, eventually withdrawn, was put that a plebiscite of growers should determine if they wanted the Committee of Direction to continue; another, on the opposite tack, suggested that the Marketing Act should be “crowned” by instituting central selling through one organization, thereby eliminating problems which had arisen in an only partially controlled selling system.

Growers also expressed dissatisfaction with being shut out of any direct voice in selecting members of the Committee of Direction. Under the Act, the Government appointed the chairman, and the B.C. Growers’ and Shippers’ Federation appointed the other two members. But that Federation, despite its name, did not in any way represent the growers; indeed, under its bylaws only shippers could be members. Many growers felt that shippers’ interests had been placed above those of growers. The 1929 B.C.F.G.A. Convention therefore passed a resolution proposing that the B.C.F.G.A. executive committee should select members with fifty per cent of the voting power on the Board of Directors of the Growers’ and Shippers’ Federation. The Federation rejected the proposal; it would agree only to two grower representatives, one for fruit and one for vegetables. These would have no voting powers, and would act in an advisory capacity only. The B.C.F.G.A. Executive felt that such limited powers were unacceptable and rejected the offer. The 1930 B.C.F.G.A. Convention again called for grower representation but the Federation still resisted.

Returns from the 1929 crop were slightly better for apples and much better for other fruit than in 1928, but confidence in the Committee of Direction had been broken, and while growers did not wish to go back to the previous state of affairs, they were again listening to new plans for marketing systems. At the 1930 B.C.F.G.A. Convention, Committee chairman F.M. Black himself spoke in favour of central selling, and suggested that a B.C.F.G.A. committee draw up a plan to present at the next convention. In the meantime he offered as an immediate improvement, a scheme of pooling returns to equalize the costs of storing and marketing surplusses not saleable on the direct domestic market. The Convention approved the proposal and requested that the Legislature make the necessary amendments to the Produce Marketing Act.

Small independent shippers continued to oppose these amendments to the Produce Marketing Act, and even the larger independents who had helped to sponsor the move through their selling agency, Sales Service Ltd., became unsupportive as the time came to implement the plan. But their real opposition was directed at a far greater threat to their way of doing business: F.M. Black’s plan for central selling. Presented in the fall of 1930, Black’s plan generated controversy and high feelings equal to, if not more than, those aroused by the 1927 Produce Marketing Act. The Black plan was basically this: a central marketing board elected by the growers should have complete control of the crop, with power to set minimum prices and control timing and destination of shipments. Associated Growers would be taken over to create the selling agency, and the private concerns would become packers only.

The debate on this plan was much like that of 1927. Supporters claimed the scheme would result in savings in overhead and selling costs, in readier financial support from banks, in better control over grades and elimination of waste, and in a stabilized market through control of the distribution of the surplus to new and distant marreduce the cost of marketing fruit from $700,000 to $300,000 a year, a saving of nine cents a package. The opposition, as in 1927, came from private sellers of fruit and from those who rejected any restrictions on their freedom to dispose of their produce however they wished.

Since the B.C.F.G.A. Executive supported the Black central selling plan, and provided a forum for its promotion at meetings of the locals, the independent shippers resolved to form their own growers’ organization. This Independent Growers’ Association held its organizational meeting at Vernon on December 20, 1930, where resolutions were passed condemning the Black central selling plan. From the start the association’s plausibility as a growers’ organization was compromised by the number of shippers in organizational positions. The Independent Growers’ Association was openly and “absolutely opposed to all forms of marketing by legislative enactment”; it not only stood against central selling but also against the Produce Marketing Act, proposing that the only governmental involvement should be a Bureau of Information to circulate market reports.

The Independent Growers’ Association claimed attendance of over 800 at its first convention at Kelowna on February 5, 1931. This convention elected General A.R. Harman, a Kelowna tulip bulb grower, as President, and passed resolutions condemning the central selling plan. But changing political conditions made central selling a dead issue, and by the end of the year the organization withered away. Its members either returned to the B.C.F.G.A., where central selling was no longer a matter of discussion, or lapsed into quiescence. By March of 1932, the Independent Growers’ Association was dormant, although it was still nominally extant until at least 1934.

The demise of the central selling scheme had come just as it seemed to triumph. Black’s central selling plan had been presented to growers’ meetings throughout the Valley, and at the B.C.F.G.A. Convention on January 22, 1931, it was endorsed by an overwhelming majority of members. A draft legislative bill, known as the “Growers’ Sales Act”, was drawn up and introduced in the provincial legislature in March of 1931, but it was killed on a technicality. In fact, central selling had been made politically inexpedient for the government by two recent events: the report of a Royal Commission and the judgement in a Supreme Court case.