News & Events More |

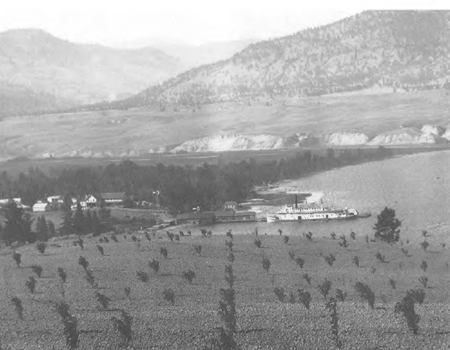

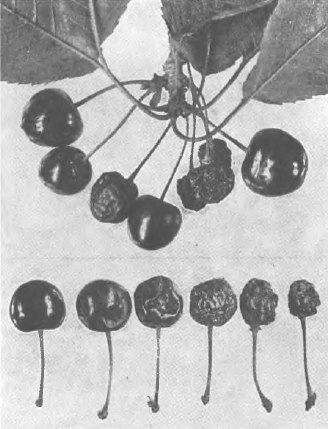

Struggling OnThe collapse of the Fruit Exchange left the B.C.F.G.A., which had been so closely associated with it, in an uncomfortable position. Membership had declined greatly during the depression of the mid-1890s-in 1896 only forty members had actually paid their membership fee-and now it was time for the Association to again demonstrate that it had a good reason for existing. The short annual meeting on January 31, 1899, did little except pass a resolution that, since the increasing production of fruit meant that British Columbian fruit growers would in future have to depend on markets in Manitoba and the Northwest (which had, up to that point, given unsatisfactory returns due to the shippers' inexperience and faulty methods), the B.C.F.G.A. should devote all of its available funds to "the sole purpose of creating these outside markets, and for ascertaining the best methods of shipping the fruit and putting these methods into practise." An Executive Committee was selected to carry out the resolution and "to formulate plans for the future work of the Association". This Committee arrived at a plan including stationing a man in the Northwest during the fruit season to report on prices and market conditions and hiring an expert on fruit packing and shipping to demonstrate proper methods throughout the province. (This was the year that Tom Wilson, provincial Fruit Inspector at Vancouver, visited Winnipeg and reported that one lot of Lower Mainland plums he saw there "appeared to have been shoveled into the boxes." 8) The B.C.F.G.A. itself would send a trial carload of plums to Winnipeg at the beginning of the season to demonstrate the best techniques of packing, cooling, and handling. The S. S. Okanagan at Penticton, about 1910. Courtesy Kelowna Centennial Museum The weather frustrated much of the B.C.F.G.A. program for the crop of 1899. The summer was extremely rainy, and brown rot, or plum rot as it was then known, was for the first time a serious problem. A.T. Bassford of Vaccaville, California, the packing expert hired by the Association, recommended against even trying the experimental carload shipment, as the plums in the Lower Mainland were in no condition to travel. He did, however, hold meetings and demonstrations at points throughout the Lower Mainland, on Vancouver Island, and in the Okanagan. The experience of those who did try to ship to the Prairies that season was disappointing. Tom Wilson concluded that much of the problem was that fruit from the Lower Mainland did not have the keeping qualities of that from the drier areas of California or Eastern Oregon. This assessment seemed all the clearer as fruit from the dry belt of the B.C. interior had fared much better than that from the Coast. Another serious impediment to successful handling was the small and scattered nature of fruit plantings in British Columbia compared to the large solid blocks in the American fruit districts: "We have no district closely contingent to the railway, where they could pluck, pack and cool a carload and have it dispatched the same day. Over there they can dispatch a trainload." Ditch irrigation at Walhachin, about 1910. Courtesy PABC In 1900 the B.C.F.G.A. was at a low ebb. The efforts of the previous year had not been very successful, and membership was falling off. At the Convention all those present were elected Directors-fifteen of them, by far the smallest directorate ever. They were urged to "one and all try and induce new members to join." The main action of the Convention was to reiterate the previous year's decision to devote all available funds to developing markets. Support for the B.C.F.G.A. was so feeble that the Directors passed a resolution at their quarterly meeting in August "that in their opinion the Association should be continued, and that they continue the work begun last year, only in a more practical manner." Vignette: Brown RotThe first fruit growers in British Columbia were troubled by few pests, but inevitably the multitude of damaging diseases and insects which can afflict fruit migrated to B.C. once orchard hosts were provided. The question, despite nursery quarantines and inspections of imported fruit, was not whether the next plague-be it apple scab, San Jose scale, codling moth, or Little Cherry disease-would arrive, but rather, when! The Brown Rot fungus (Monolinia fructicola), which prefers the soft fruits and thrives in warm, humid conditions, first infected a few Lower Mainland orchards in 1898. The following two seasons, both unusually rainy summers, established it as a scourge throughout the Fraser Valley because the infection continued to spread after the fruit was packed and shipped. Plums from the Lower Mainland arrived in Winnipeg with brown rot in every case. Efforts to check the disease with repeated sprays of Bordeaux mixture, made of copper sulphate and lime, were only partially successful. Fruit deteriorated so much on the way to market that the Winnipeg wholesalers suggested that plums should be shipped only from interior districts such as the Okanagan, where the disease had not yet appeared. Growers in the Lower Mainland were so alarmed by the threat to their principal tree fruit crop that one of them gloomily told the B.C.F.G.A. convention of 1901 that there was no point in discussing matters of marketing on the Prairies "until we can establish the fact that we can send a carload of plums."  Brown rot on sweet cherries. Courtesy Country Life in B.C. Once infected, an orchard was in danger whenever weather conditions suited the growth of the fungus, for spores can arise for up to ten years from "mummies", those shrivelled up infected fruits left by the pickers which fall to the round and incubate the disease. In warm, wet weather brown rot can destroy half or more of the crop in an orchard in less than a week. The helplessness of growers against brown rot was reduced with the discovery in 1907 that sulphur, used either as a lime-sulphur mixture or later in the form of wettable sulphur powder, gave better control without the damage to fruit done by the caustic Bordeaux mixture. However, for truly effective prevention of post-harvest brown rot, growers had to wait until the era of synthetic chemicals following the Second World War. "Captan", the first of what is now an extensive range of fungicides, made its appearance in 1952. It had been discovered by accident when Dr. Allen R. Kittleson, a research chemist for the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, submitted a random sample of an untested chemical to the company's biological laboratory for fungicidal screening as a joke! To his surprise, the sample turned out to be effective against a wide range of fungal diseases, and "Captan" is still used to control brown rot in stone fruit, apple scab, and a number of other fungal diseases of fruit. So, thanks to "Kittleson's Killer", growers today seldom experience the sickly smell of concentrated brown rot, nor do they watch clouds of spores puffing off the fruit in their hopelessly infected crops of plums, peaches, or cherries. The annual meeting of 1901 reiterated the Association's resolve to develop markets, endeavoured once more to agree on standard sizes for fruit boxes, and, as usual, complained of high freight rates. During the fruit season, an expert fruit packer, B.G. Stoddard, was employed and gave practical lessons on grading and packing at twenty-six places, and the B.C.F.G.A. succeeded in gathering an experimental carload of fruit which travelled to Prairie markets in the care of J.C. Metcalfe. This refrigerated car, only partly iced due to an ice shortage at the loading point, left New Westminster on September 9th loaded with 805 crates of prunes and 80 boxes of pears. After six days in transit, the fruit sold at Winnipeg at 45 cents a crate, ten cents better than the price on local markets, "and Mr. Metcalfe assures us that had the brown rot not appeared he would have had no difficulty in getting 50 cents." The experiment was accounted a success, as it showed that, properly handled, fruit could be shipped in carload lots as far as Winnipeg and sold there at a profit. Premier Richard McBride's lot on the Middle Bench, Penticton, 1907.Courtesy Penticton Museum Despite the success of the Association's activities in 1901, membership had dwindled further, and when the 1902 annual meeting decided that all members should be directors, it was noted that this made a Directorate of only 28. Various papers on horticultural topics were received, and the previous year's program of packing demonstrations and trial shipments of fruit continued. Four carloads were shipped under the auspices of the B.C.F.G.A. in 1902. An exhibit of three tons of fruit was sent to the annual exhibition of the Western Horticultural Society in Winnipeg, which drew favourable publicity for B.C. fruit. At the Association's request, an Inspector was appointed to enforce the federal "Fruit Marks Act", passed in 1901, which required all fruit packages to be marked with variety, grade, and the name and address of the shipper. As a result of this activity, membership picked up, and by the 1903 annual meeting there were 161 members, "and with one or two exceptions all are actively engaged in the work of fruit-growing; whereas in former years, the membership was made up largely of professional and business men who had no actual interest in the business of fruit-growing." Due to lack of funds, the packing demonstrations and the carload shipments were not repeated in 1903, although the Association did send displays of fruit to Regina, Brandon, and Saskatoon to publicize the British Columbia product. During 1904 and for several years following, the activities of the B.C.F.G.A. were largely limited to horticultural discussions at the annual and quarterly meetings, to informational meetings demonstrating proper techniques to fruit growers, to promotional displays of British Columbia fruit, and to the formation of local cooperative Fruit Growers' Associations, which would affiliate with the provincial body. Also, for the first time in 1904, the B.C.F.G.A. went into the supply business, selling fruit wrapping paper and importing a shipment of chemically pure copper sulphate from England, "with a view to demonstrate the great value of the chemically pure article over that usually sold by the trade". This activity was continued and expanded for several years; in 1908 the Association sold $1073 worth of spray materials and $353 worth of fruit wrapping paper. Contact Us Hours: 9am - 4pm weekdays. t: 250-762-5226 |